What's Next for the FTC's Proposed Privacy Framework?

The December 2010 release of the FTC's much anticipated Privacy Framework (see our coverage here, here, here and the report itself here), included the typical public comment period, which ended in February. We've looked at the 442 separate submitted comments received by the FTC, available here, from individuals and associations, corporations and organizations. The goal was to uncover what themes, trends and thoughts are raised by the FTC's framework, and in turn, to scope what feedback the FTC will be weighing in future changes of the report and ultimately any resulting recommendations for additional legislation and regulation. Why spend the time now, rather than waiting for future concrete statutes and regulations, particularly in light of the ongoing bills recently proposed at both the state and federal levels (see Speier bill here, Boucher bill here, Washington's PCI law here, Colorado's novel data bill here, etc.)? Because the FTC has a front and center role in the ongoing online privacy debate - one recently joined in earnest by the Department of Commerce and the issuance of its privacy "Greenpaper" report. As such the FTC's opinion, and its effect on industry actions, is outsized. And since IT budgets, plans and implementations have long range time horizons, advance understanding of what may come, in one form or another this year or next, should help avoid the need to embark on costly sudden reactions. With this in mind, what can the public comments tell us?

As part of our survey, we reviewed each and every one of the 442 submitted public comments, from commenter and organizations both domestic and overseas, as well as the additional 7 late filed comments. In total we downloaded 107MB of PDFs representing the comments of nearly 200 organizations, associations, corporations, universities and other entities. What major themes emerged?

- Prepare for Do Not Track - or Maybe Not

- Companies “Support” the FTC

- The Academy and Associations Weigh In - Big Time

- Keep Watching the States!

- The FTC will define with specificity 'precise geolocation data' in the next Framework

UPDATE: 3/25/11 - The last two days have seen a flurry of activity connected to the FTC and the Privacy Framework. First, a very early public draft of the Senate "Commercial Privacy Bill of Rights Act of 2011, was introduced by Senator Kerry, which we covered earlier this week, here, in the wake of testimony on March 16th by Jon Leibowitz, Chairman of the Federal Trade Commission, before the Senate last week (PDF of his testimony here). Complicating the picture further is the fact that FTC Commissioner J. Thomas Rosch, who in the original framework supported release of the FTC Framework as a "hortatory exercise" in the furtherance of discussion on privacy, but distinctly disagreed with many of the proposals put forth has an editorial in AdAge magazine, here, wherein he stated yesterday that:

"The concept of do not track has not been endorsed by the commission or, in my judgment, even properly vetted yet. In actuality, in a preliminary staff report issued in December 2010, the FTC proposed a new privacy framework and suggested the implementation of do not track. The commission voted to issue the preliminary FTC staff report for the sole purpose of soliciting public comment on these proposals. Indeed, far from endorsing the staff's do-not-track proposal, one other commissioner has called it premature. I also have serious questions about the various do-not-track proposals. In my concurring statement to the preliminary staff report, I said I would support a do-not-track mechanism if it were "technically feasible." By that I meant that it needed to have a number of attributes that had not yet been demonstrated. That is still true, in my judgment."

Point #1 - Prepare for Do Not Track - or Maybe Not.

UPDATED: 3/25/11 - See above. The individual comments received range from the pithy “Yes! Pursue this” and “I do not want to be solicited” and “Cookies make the consumers [sic] life easier Keep cookies!!” to impassioned and well-reasoned submissions strongly urging the FTC to implement some form of “Do Not Track” or opt-in rather than opt-out mechanism. Many individuals referenced the Wall Street Journal's groundbreaking series on digital privacy, What They Know, as evidence of the widespread information tracking and data exchange occurring “behind the scenes” by many applications, both those on the desktop and in smartphone apps.

A distinct minority of individual submissions, not otherwise provided on behalf of an entity, association or organization, did not support the FTC's proposed “Do Not Track” scheme or the FTC's broader goal of provided users with more transparent and immediate control over the gathering of information related to their online habits.

Shortly after the FTC Privacy Framework's release and its “Do Not Track” proposal, the response in the market, among privacy advocates, analysts, and the public and web browser companies was robust to say the least. Several major web browsers, apparently reading the handwriting on the wall, announced support for a browser-based means of defeating persistence online tracking.

Mozilla, the author's of the popular Firefox browser, announced plans to incorporate a Do Not Track feature into their Firefox 4.1 browser release, and publicly stated in direct response to the FTC support for “[a]doption and creation of a uniform and comprehensive choice mechanism through a new Do Not Track (DNT) HTTP header as part of an evolutionary arc of privacy improvements” (here). Mozilla also submitted public comments – albeit late - to the FTC as discussed below.

Microsoft likewise added Do Not Track header and other support in its new Internet Explorer 9 browser via its “Tracking Protection” features (see here), and similarly submitted comments to the FTC (below).

In parallel, the Web Tracking Protection group of the World Wide Web Consortium, a longtime web standards body (W3C), solicit technical discussions on establishing a DNT standard (see Microsoft's technical DNT submission here).

As of this writing neither Apple via its Safari browser, nor Google, via Chrome, have formally announced specific DNT support or technology. However, Google announced a Chrome extension “Keep Your Opt-Outs” in an attempt to address cookie-based opt-out schemes, and noted this extension, as well as discussing “Do Not Track,” in its nine-page of comments to the FTC.

As further examined below Google, in its public comments to the FTC, somewhat attempting to get its horse ahead of the gathering momentum of the rolling DNT cart, tentatively embraced the DNT concept and highlighted its rather nascent Ads Preferences Manager in response. Query on page 5 of Google's comments: “Long before the current discussion about 'Do Not Track,' Google was offering an industry-leading transparency and control tool for its IBA [Internet-based Advertising] system.” Perhaps, but was it a "successful" or "well-known" tool?

As always the devil is in the details, and while I expect Do Not Track to become a reality in the relatively near future, the means, methods, defaults and how traditional HTTP cookies, flash cookies and other supercookies, bugs, JavaScript trackers, HTTP Referrers, and more importantly, device fingerprinting will be addressed in the aggregate remains an open question.

Point #2 – Companies “Support” the FTC

Read enough corporate submissions responding to any governmental request for public comment and you could reasonably be excused from concluding companies love government regulation, embrace active intervention, are happy about increased reporting mandates and firmly believe that the work of the agency in question is nothing short of bold, ground breaking, fully informed, and the scintillating product of the most brilliant paragons working today in the specific arts and sciences involved.

Conversely, those on the cynical side are more apt to believe that every corporate submission is driven first and foremost by whether: (I) the proposals being put forth ultimately result in either growth or decline for the company's market; (ii) the agency and company clients/users are likely to be positively disposed to public support of the proposals; (iii) and, whether the proposals are more likely to negatively effect competitors than the submitting company.

Somewhere in between these two polar extremes fall the corporate responses of Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Mozilla, Intuit, AT&T, Experian, eBay, Intuit, EMC, IBM, VISA, Verizon, Yahoo, Honeywell International, Avery Dennison, Truste, LifeLock, ClickZ, and others. Interesting Intel, for all its tech prowess appears not to have mastered the art of PDF scanning, given its submission weighed in at a mammoth 15MB - nearly double the size of the next largest submission.

An exhaustive look at all is more than any of us outside the FTC are inclined to willingly submit to, but from the corporate submissions several themes emerge: caution regarding locking in any one set solution, especially a “solution” reliant on any single technology; general support for Privacy-by-Design and Do Not Track, albeit in various shades and levels of backing; uneven though vocal support for Fair Information Practices; and a desire for reasonably achievable compliance founded on flexibility of approaches to enhance privacy and security. Let's take a high-level view of a handful of representative submissions from: Facebook, Google, Microsoft and IBM.

As the current titan of social networking Facebook has come under regular scrutiny and criticism for its various privacy policies and practices of sharing of users' data (see Facebook Broadcast Private Phone Number and Address Data, Can You Really Trust Facebook?). In its 29-page submission Facebook focused on “balance” to protect privacy without imposing “privacy restrictions [that] could limit Facebook's ability to innovate” while recognizing what would conversely occur should Facebook fail “to protect the privacy of its users adequately” because “those users will lose trust in Facebook and stop using the service.”

In Facebook's view of the ongoing privacy debate “the areas of consensus far exceed the remaining areas of disagreement” with Facebook stating it shares with the FTC (and the Department of Commerce Greenpaper, given Facebook expressly notes its response “incorporates key elements from both the FTC and Department of Commerce proposals”) a “common focus” on three main principles:

- Integrated Privacy Protections: Companies should incorporate context-sensitive privacy protections throughout their organizations and products.

- Individual Empowerment and Responsibility: To enable individuals to make the privacy decisions about information that are right for them, companies should provide a combination of greater transparency and meaningful choice appropriate to the context in which information is collected.

- Industry Accountability: Robust industry self-regulatory efforts, in combination with judicious enforcement by the FTC, can address users' privacy concerns while providing sufficient flexibility to accommodate rapidly developing technologies and user expectations of privacy

Facebook's comments boil to down urging the FTC (1) that context is the key to ensure “privacy protections benefit, rather than frustrate, users' needs and expectations,” and (2) any ultimate privacy framework, revolving around users' choice and correspondingly their own accountability should “promote rather than stifle the innovation that has been so essential to our economy.”

The remaining 25 pages of Facebook's submission includes detailed background and historical analogies, which make for interesting leisure reading, and thoughtful commentary on notice-and-choice, potentially enhanced choice for sensitive data, and improved privacy notices, but the preceding sentence captures the distilled essence of Facebook's view, particularly as Facebook broadly opines that common Do Not Track “concerns are not implicated when the user has a relationship with the company [i.e. Facebook] conducting the tracking and understands that the entity may be collecting data.”

Google's 9-page submission is admirably succinct, but is openly a showcase of “how the Commission’s proposed framework can help strengthen privacy practices and how Google has incorporated the framework principles into our offerings.” Still, who doesn't appreciate the direct approach? Perhaps Google at some level believed any submission other than one saying “we want to help, too, and here's how” would strike many as a bridge too far, in light of the fact that as the current 800 pound online gorilla the bulk of its income hails from targeted internet advertising and aggregation of user searches and website visit practices. Fair enough, though to be impartial Google does step through its thoughts on “how standard and practices can develop to better match” the principle that “companies should incorporate consumer privacy into product and service development, and promote it within the culture of a business” - a nod to the FTC Framework's Privacy-By-Design proposal.

To this end Google maintains security is one of “Google's five foundational privacy principles.” (The other four being: 1. Use information to provide our users with valuable products and services; 2. Develop products that reflect strong privacy standards and practices; 3. Make the collection of personal information transparent; and 4. Give users meaningful choices to protect their privacy http://www.google.com/intl/en/corporate/privacy_principles.html). Several of the items Google highlights thereafter in its products and services are:

- Google is the only major search provider that enables users to encrypt search queries (i.e., just type in https://www.google.com which maps over to https://encrypted.google.com)

- "Google remains the only major webmail provider to offer session-wide SSL encryption by default, which protects Gmail users worldwide from improper access to or surveillance of their communications. And recently released a 2-step authentication for consumer Gmail accounts where users concerned about account security can use a password plus a unique code generated by a mobile phone to log in. "

While agreeing with the FTC that privacy discussions have moved away from the opt-in/opt-out notice and consent existing framework to a large degree, which Google welcomes, Google does note a small measure of disagreement with the FTC Framework singling out interest-based advertising and questions the utility of such a mechanism by calling for “the Commission, industry, and other stakeholders to continue to engage on improving solutions for users in this area, lest bad actors and confusing practices create distrust in advertising-supported services.”

Sidling away from the FTC Framework and up to the Commerce Department Greenpaper, Google comments on the Electronic Privacy Communications Act (“ECPA”) stating it has “significant constitutional concerns about a law that permits government access to the content of communications with less than a warrant,” and urging the FTC to petition Congress, via Google's membership in the Digital Due Process Coalition, “to update ECPA in a manner that ensures its protections are consistent with privacy expectations and constitutional requirements.”

Microsoft's 19-page submission is classic Microsoft (MS): technical, replete with dense content and, of course, a presentation-ready diagram. Always expect a diagram from the makers of PowerPoint.

Microsoft's comments focus on urging the FTC to enact or consider a number of points. First, MS supports limited exceptions for those companies that collect, use, store or disclose personal information from fewer than 5,000 people in any 12-month period and use that information “only for purposes that are reasonably necessary for the operation of the company, such as product fulfillment, protecting the rights of the company and third parties, and first-party marketing.”

It also urges the FTC to ensure businesses have the “flexibility to select appropriate anonymization or de-identification methods based on the context, including the type of information that is being collected, how this information will be used, and the relationship that the business has with the consumer.” In proposing this MS notes that “for consumers who have created Windows Live accounts, rather than using the account ID as the basis for our ad systems, we use a one-way cryptographic hash to create a new identifier” which is then combined with non-identifiable demographic data, according to MS, to serve online ads.

On the search side, MS states that at its Bing.com search engine it permanently removes the entire IP address from all Bing search query data after 6 months, and after 18 months “we take the additional step of deleting all other cross-session identifiers, such as cookie IDs and other machine identifiers, associated with the search query.” In a footnote MS takes a swipe at longer data retention of addition cross-identifiers that “could permit the correlation of sufficient search data related to an individual consumer to make it possible to identify such an individual even without an IP address or without what would traditionally be considered personally identifiable information.”

MS fully embraces the FTC's “privacy by design” (PbD) approach and “supports an industry-wide privacy-by-design principle that encourages businesses to incorporate privacy protections into their data practices and to develop comprehensive privacy programs.” In doing so MS pats itself on the back a bit, stating its “commitment to privacy by design is deep and long-standing.” Objectively I can't argue with this self kudo, given that after numerous security problems, issues and weaknesses that made headlines in its various Window OS versions over the years, coupled with chronic security holes in the Internet Explorer browser family on the road to the just released IE9, MS can truly be said to have taken its share of security-related arrows and demonstrably took data security and privacy to heart – whether it's always successful is another matter. In further support of its bona fides here MS states “our privacy guidelines are part of the foundation for one of the International Association of Privacy Professional’s privacy certifications – the Certified Information Privacy Professional for IT (CIPP/IT).”

Finally, as to PbD MS “urges the Commission to avoid imposing prescriptive requirements with respect to data retention periods or in further defining 'specific business purpose' or 'need'” because “any limitations on data retention and use must focus on accountability and on accommodating and encouraging evolving or innovative technologies and business models over time.”

MS's comments continue is a similarly detailed fashion, covering “commonly accepted practices” that would not require consent with the cautionary truism that “what is 'commonly accepted' changes over time, sometimes fairly rapidly, as technology, business models, and consumer adoption and usage of services evolve.” From there on it supplies analysis of “practices that require meaningful choice” and thence onto Do Not Track, which Microsoft supports in a cautionary fashion: “urg[ing] [FTC] staff to remain technology neutral and to avoid preferring any particular 'do not track' mechanism over others” due to the fact that “[g]iven how rapidly behavioral advertising evolves * * * [a]ttempts to require the use of a particular 'do not track' technology may quickly become obsolete and could chill innovation in the development of new technologies and mechanisms for providing consumer choice.”

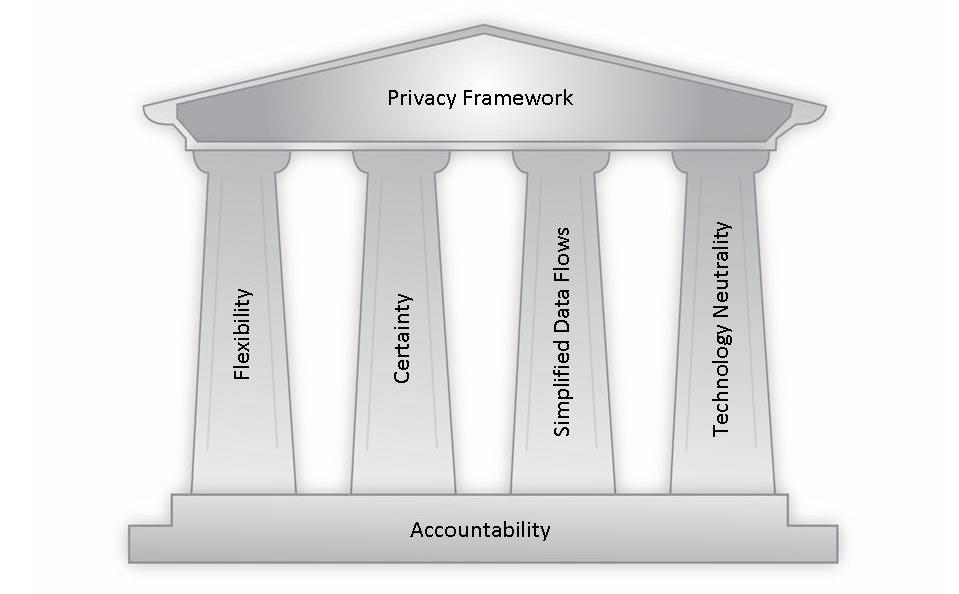

Overall MS's comments are among the most substantive and concrete, and are worth reviewing. What about that diagram? Well, Microsoft states its “overall views and suggestions regarding the FTC’s privacy framework are illustrated in the below diagram. The framework should be supported by a foundation grounded in the concept of accountability. Building on this foundation are the four criteria by which the overall privacy framework is measured: (1) flexibility, (2) certainty, (3) simplified data flows, and (4) technology neutrality.”

IBM.

Having been on the computing scene since nearly day one in the U.S., Big Blue remains a significant player today on the technology front, even though it can't match social networking and search engine newcomers in the hip quotient. As such one can expect staid, informed, measured commentary from the company that once was synonymous with a safe tech choice, and IBM doesn't disappoint.

Its comments begin, “IBM generally supports the principles of the proposed framework: privacy by design, simplified consumer choice, and greater transparency as to commercial data practices.” No surprises so far. Its further suggestions to the FTC continue, and read rather like a wise-Uncle's recommendations: 1) remain technology-neutral; 2) make compliance reasonably achievable; 3) offer clear safe harbors; 4) clearly distinguish between those businesses that control data and those that are service providers; 5) be consistent with cybersecurity objectives; 6) include a broad preemption provision; 7) provide effective and workable protection; and 8) be enforced exclusively by federal regulators.

Regarding the development and launch of mechanisms to promote transparency and informed privacy choices, IBM recommends: a) standardized ways to compare privacy policies; b) balanced restrictions and purposes specifications (and support of exempting “common accepted” practices, which IBM says “should be defined to include those things that companies must do to fulfill its transactions, to market to consumers on a first party basis, to comply with legal requirements and to prevent fraud”); c) providing effective notice and choice; d) encouraging mechanisms by which consumers can make their choices effective across the board, rather than site-by-site (“the proposed 'Do Not Track' mechanism is an example of this approach” though IBM further cautions “this issue is far more complex than the 'Do Not Call' legislation to which it is so frequently compared”); and e) maintain parity among marketing channels.

In concluding, IBM blesses the FTC's Framework, but again issues a caveat, saying the Framework: “rightly calls for simplified consumer choice and improved transparency in data practices. * * * At the same time, the Commission’s proposals are made against a background of rapid change, both in technology and in consumer expectations and wants. We have offered the foregoing comments in the confidence that improved consumer privacy can be achieved without technological mandates and without sacrificing flexibility and support for innovation.” Together the above submissions represent a reasonable sampled spectrum of the tech corporate community, and I think highlight the commonalities, as well as the differences, in opinion of those who could be most directly effected by any resulting “binding” FTC-led framework that results, whether via regulation or legislation.

Point #3 - The Academy and Associations Weigh In

The FTC final tally of public submissions reveals no shortage of commentary from academia and various associations. Numerous detailed, highly technical and professionally formatted PDF submissions, some over 45 double-spaced pages, arrived from various legal counsels across a veritable who's who of online and privacy focused organizations and trade associations. Much of the comments proved relatively straightforward in focusing on specific issues, while several read like, and indeed are, academic theoretical papers noting eye-glassing observations such as “[t]he distinction between explicit and implicit data transfer can be partially disambiguated by examining the corresponding actions that would need to be taken by the firm and the consumer if such a transfer was occurring in a non-electronic (or “physical world”) setting.” Do I hear a vote from the normative contingent of the peanut gallery?

Submissions were provided by, brace yourself, to name but a few:

The Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, Internet Commerce Coalition, EPIC (Electronic Privacy Information Center), EFF (Electronic Frontier Foundation), ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union), American Catalog Mailers Association, American Bar Association and its Section of Science & Technology Law (of which many attorneys at the InfoLawGroup are members, though the ABA and this section does not necessary reflect the opinions of our firm, our individual attorneys, or our clients), the Direct Marketing Association, CASRO (Council of American Survey Research Organizations), Business Software Alliance, CTIA - The Wireless Association, Electronic Retailing Association, Email Sender & Provider Coalition, American Trucking Associations, Future of Privacy Forum, Food Marketing Institute, Interactive Advertising Bureau, Online Publishers Association, Consumers Union, Center for Digital Democracy, Consumer Federation of America, Consumer Bankers Association, Coalition of Trade Associations, National Retail Federation, Magazine Publishers of America, Mortgage Bankers Association, National Cable & Telecommunications Association, National Association of Manufacturers, Information Technology and Innovation Foundation, Newspaper Association of America, Marketing Research Association, PhRMA, Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, Carnegie Mellon University, Ohio State University, New York University and its School of Law in a separate submission, and several submissions from abroad by the Office of the Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario, the UK Information Commissioner's Office, and ENACSO – European NGO Alliance for Child Safety Online.

There is no reasonable way to do justice to the voluminous submissions, except to highlight a very few notables that stood out in my opinion.

- The Berkeley Center for Law & Technology, via Chris Jay Hoofnagle, Lecturer in Residence, urges the adoption of basic benchmarks to evaluate tracking and the FTC's approaches. He further suggests adopting of a nuanced and “different framing on consumer attitudes towards privacy” rather than the Alan Westin-based methodology used by the FTC. More concretely, he suggests that certain key terms, often found in privacy policies and Terms of Use, must confirm to a standard definition (highlighting California's “'Shine the Light Law,” which requires disclosures surrounding third party marketing disclosures”).

- CASRO, an organization that represents 350 research companies engaged in market research, stresses a continuation of self-regulation in the research field, highlighting the existing CASRO Code of Standards and Ethics for Survey Research.

- The Center for Democracy and Technology stresses that “it is time to define what 'track' actually means in the context of Do Not Track,” and offering a “preliminary effort to scope what 'track' should and should not communicate in the context of browser-based DNT mechanisms.” The CDT states its proposals draws on “definitions and ideas found in a diverse set of sources, including the the FTCʼs online behavioral advertising self-regulatory guidelines, Interactive Advertising Bureauʼs online behavioral advertising self-regulatory guidelines, Rep. Bobby Rushʼs 2010 consumer privacy bill (the BEST PRACTICES Act), CDTʼs online advertising threshold analysis, and documents that CDT has produced through its work in technical standards bodies.”

- The Consumer Bankers Association opines that a new U.S. Framework is not necessary, and “[t]o the extent a new framework is contemplated, . . . the FTC should look to the cornerstone of privacy for financial institutions, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act (GLBA) as a model, as it strives to achieve the correct balance between providing important privacy protections for consumers with the understanding that certain information sharing is necessary and appropriate.”

- Electronic Privacy Information Center (EPIC) stresses the “FTC should pursue meaningful investigations and enforce Section 5 fully” thereafter providing, as one of five examples of the FTC's failure, EPIC's 2009 complaint against Google's Cloud Computing services, which EPIC states the FTC failed to act upon and criticizing that “to the extent that the FTC has shown an interest in this topic [cloud computing], it has largely been to discourage investigations by other agencies.”

- The Interactive Advertising Bureau, which represents more than 470 companies active in the support and sale of interactive advertising, “believes that the appropriate approach to addressing consumer online privacy issues is through industry self-regulation and education. Existing and emerging robust self-regulatory principles address privacy concerns while ensuring that the Internet can thrive, thereby benefiting both consumers and the U.S. Economy.”

- The Mercatus Center at George Mason University make the humorous, but often true, observation that “How Do We Conduct Cost-Benefit Analysis When 'Creepiness' Is the Alleged Harm?” I highly recommend reading “the whole thing” as they say.

As you can see I've only literally scratched the surface of this category of public comments received by the FTC, but the submissions I reviewed are by and large a real testament to and display of the commitment, high level of deep thought, and broad ranging considerations that make plying the legal waters of the data security and privacy arenas such a day-to-day fascinating place.

Point #4 - Keep Watching the States!

In a letter authored by the Attorney General of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, but joined by the Attorneys General of 14 other states (Arizona, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Tennessee, Vermont, Virginia, and Washington), the AG's “support the protection of consumer privacy” and write to (a) request no federal pre-emption by “any federal laws or regulations protecting consumer privacy that are adopted as a result of” the FTC Framework, and (b) focus “on three main questions raised by the FTC in the Report's Appendix A:

- Are there substantive protections, in addition to those set forth in Section V(B)(l) of the report, that companies should provide and how should the costs and benefits of such protections be balanced? (A-I);

- How should the scope of sensitive information and sensitive users be defined and what is the most effective means of achieving affirmative consent in these contexts? (A-3); and

- Should additional protections [of teenagers] be explored in the context of social media services? (A-4).”

Additionally, in a reverse echo of the geospatial contingent's angst, below, over no FTC-provided definition for "precise geolation data” the AG's “strongly encourage the FTC to explore further whether location based data, which is capable of tracking a person's movements, should be considered sensitive information.” However, in a move guaranteed to put this group into direct conflict with the vocal geospatial community, not to mention Google Latitude and other mapping schemes, the AG's further state “the FTC should explore whether there is any legitimate purpose for 'location-based data' to ever be stored or retained by those who gather it.”

The past several years have seen a renewed resurgence of state action on the data privacy and security front, and if the AG's letter to the FTC is any indication this will not diminish any time soon.

Point #5 – FTC will define 'Precise Geolocation Data' in its Next Framework

The single largest collective “group” response, other than individuals, that populate the public comments came from the private geospatial and geolocation communities, which the FTC's framework put into a lather.

Led by the Centre for Spatial Law and Policy, Coalition of Geospatial Organizations (COGO) and MAPPS, the Management Association for Private Photogrammetric Surveyors, along with numerous comments from individual surveyors, aerial mappers and other geospatial companies, this group unanimously honed in on three words of the FTC's Framework: “precise geolocation data.”

The phrase appears almost in passing where the Framework discusses “sensitive information” in the broader context of whether such items should received affirmative express consent for collection on page 74-75:

“The Commission staff has supported affirmative express consent where companies collect sensitive information for online behavioral advertising and continues to believe that certain types of sensitive information warrant special protection, such as information about children, financial and medical information, and precise geolocation data. Thus, before any of this data is collected, used, or shared, staff believes that companies should seek affirmative express consent. Staff requests input on the scope of sensitive information and users and the most effective means of achieving affirmative consent in these context.”

MAPPs protests in its comment submission that “[o]n one hand, the term could mean actual street/house address or on the other hand, the actual location of the individual at any given time, i.e. location provided by cell phone triangulation or some other method. If the geolocation refers to a person's name and address being private, then it is inconsistent with virtually every 'open records' law in the United States, and could potentially shut down the nation’s commercial aerial and remote sensing satellite market and prevent our member firms from collecting, hosting or distributing ownership information.”

This serves to highlight how closely the reports of agencies with regulatory and enforcement authority, like the FTC, are scrutinized by groups and associations. More likely the FTC's inclusion of “precise geolocation data” was a placeholder nod to location-based tracking and information increasingly sent out by GPS-enabled smartphones. But words matter. Definitions define. And entities are wary of any governmental action that could effect their industry.

In response COGO, as with other submissions from the geolocation community, requested either a narrow specific definition of “precise geolocation data” or exemption from any FTC regulations otherwise “[f]ailure to do so would prevent some common, justifiable, and emerging uses of geospatial data for emergency response/post disaster remediation, insurance, environmental protection, E-911 & ambulance services, fleet management, broadband mapping, home security, navigation, mortgage foreclosure monitoring/early warning system, and many others.”

MAPPs went a step further in proposing a long definition of what should not come within “precise geolocation data/information” and requested the “FTC to either remove any reference to 'precise geolocation data', more specifically and exactly define the term [presumably along the lines of its proffered anti-definition],” while COGO urged that “geospatial data should also be excluded from having to be subjected to consent or waivers” along the lines of the FTC's note on page 5 of the Framework that “Companies should not have to seek consent, for example, to share your address with a shipping company to deliver the product you ordered.”

In short, expect the FTC to address geospatial and geolocation issues further within any broader online privacy framework moving forward, though as noted above, the State Attorneys General, like the FTC, appear to have completely missed the broader concerns of this group.

Conclusion.

The FTC's Framework, Protecting Consumer Privacy in an Era of Rapid Change: A Proposed Framework for Businesses and Policymakers, here, has marked a fresh milestone in the ongoing debate regarding online privacy and reasonable measures that may be needed moving forward. Along with the Commerce Department's bookend report, Commercial Data Privacy and Innovation in the Internet Economy: A Dynamic Policy Framework, here, I continue to believe that the two reports, when in final form, will be very influential in shaping legislation to come, and is why we took the time and effort to review the pubic comments recently submitted to the FTC Framework. We hope you found our review helpful, and to discuss the report, the FTC's current privacy and associated requirements, or any of the above comments, please feel free to contact me or any of the attorneys at the InfoLawGroup.